Anam Parvez Butt is a Gender Justice Research Lead in the research team at Oxfam GB. Gopika Bashi is the Asia Campaigner for the Enough Campaign at Oxfam International.

As researchers and campaigners in development organisations we constantly grapple with the question of how to design research that is useful to influencing change. At Oxfam, we’ve been thinking a lot about this, especially in the context of our worldwide Enough campaign in over 30 countries, which seeks to shift harmful social norms that justify gender-based violence through context-specific and relevant national campaigns.

Social norms are the unwritten rules that govern behaviour; the deeply held shared beliefs about what is considered normal, acceptable and appropriate ways of thinking and behaving that often drive behaviour. Shifting social norms, particularly creating positive and progressive ones, is critical to our work, and requires a different approach to more traditional campaigning.

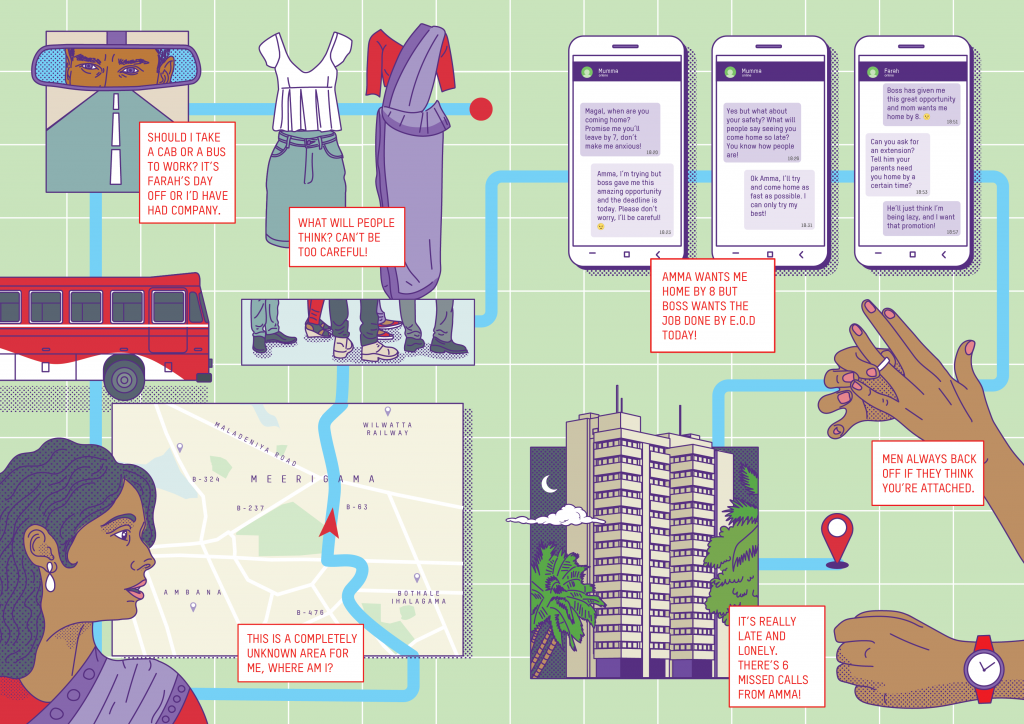

Last week, we launched the report ‘Smashing Spatial Patriarchy’ which explores the belief systems that legitimise, excuse and drive violence against women, girls, transgender and gender non-conforming people on public transport in Sri Lanka.

In Sri Lanka, 90 percent of women and girls have been sexually harassed on buses and trains at least once in their lifetime and over half say they have experienced violence on a regular basis. The research directly informed the strategy of a national-level Enough campaign, titled ‘Not on My Bus’, which was launched by Oxfam and local partners in March 2019.

As a researcher & a campaigner involved in this journey, we’ve come up with 5 tips on how to ensure the research process genuinely supports social change.

1. Link research with the campaign strategy

Research objectives must line up with the goals of the campaign. This means being clear about knowledge gaps and understanding how the evidence generated will be used. This might seem like an obvious starting point but without this, we risk having to retrofit research findings into existing campaigns.

Right at the start of campaign design in Sri Lanka, a diverse group of researchers, activists, young people and campaigners came together to map out existing information and identify evidence gaps. Two key issues emerged: firstly, the lack of research around non-partner violence in public spaces- an increasingly relevant in the context of rising urbanisation. Secondly, the absence of studies that probed deeper, beyond questions of prevalence, to understand the social norms and belief systems that are fuelling violence.

towards harassment experienced in public transport as well as prevailing

issues around reporting harassment.

This helped us design the research and clarify campaign strategies – who the campaign’s target audience needed to be, and how we could influence them by drawing on the evidence from the research. As we progressed through the research process, our multi-disciplinary and multi-locational team ‘plugged in’ during different phases. This allowed us to develop shared ownership and a consistent process of feedback and learning. Additionally, as part of the literature review, we analysed existing campaigns that have achieved some success in shifting norms around sexual harassment in public, and to identify campaigns that have not had success and why. From South Asia alone, we were able to identify feminist-led campaigns like ‘Why Loiter?’ in India, and ‘Girls at Dhabhas’ in Pakistan as excellent examples of rights-based campaigns, grounded in feminist principles.

2. Adopt a gender transformative and participatory approach to research

We embedded feminist principles throughout the research process to ensure that the research identifies issues and proposes solutions that are locally relevant and rights-based. This meant ensuring researchers and facilitators were from the communities in which research was being conducted. An independent Sri Lankan feminist activist and researcher co-conducted and co-authored the final research. Also, the focus group discussion with LGBTQI people was facilitated by someone who self- identified as queer. This was critical to establishing greater trust with the community.

Community members were engaged not only in the data collection phase as research participants but as analysts making sense of the data and as agents of change identifying solutions to their problems. The research instruments, namely the ‘Social Norms Diagnostic Tool’ were adapted with partners to reflect local realities.

3. Understand how social norms interact with other contextual factors to drive behaviours

Harmful behaviours are influenced not only by social norms but other interlinked structural, social, material and individual factors. The research explored these intersecting factors and their impact on social norms. As well as gender, we analysed data across intersecting forms of oppression, including age, location, religion, ethnicity, class and position in community that reinforce and exacerbate harmful norms.

We found that urbanisation as a result of increased economic opportunities and women’s participation in public life has increased their exposure to sexual exploitation and violence.

Meanwhile more than half of those we surveyed in Sri Lanka were aware of the law against sexual harassment. However, existing data shows that just 8 percent of women and girls in Sri Lanka who experienced violence on public transport reported it to the police, fearing further blame and humiliation. A whopping 82 percent of bystanders said they rarely intervened when they witnessed abuse.

This showed that the problem of sexual harassment is becoming increasingly relevant on transportation in urban Sri Lanka and that an individual’s awareness of the law is not enough to change behaviour. Campaigners need to try to transform the social norms that are enabling and sanctioning sexual harassment.

4. Link participatory research validation to campaign planning and design

To design strategies for norm and behaviour change, research needs to not only identify the norm and its prevalence (how many people in a group hold a belief) but also its level of influence (how many people do ‘x’ because of the norm) and how easy/difficult it would be to shift.

The two strongest norms to emerge from the research and validation workshop with participants were firstly that women who dress “indecently” invite harassment and secondly that bystanders should not intervene as it is none of their business and doing so would make matters worse.

The research validation workshop was immediately followed by a campaign planning workshop where the same participants were able to analyse not just the veracity of the norms, but also how relevant and ‘campaignable’ they would be. Campaignability was assessed through discussions across different criteria unique to social norms campaigning (for example, is the norm a ‘low hanging fruit?’, can communities be mobilised around shifting it?, is it a ‘public’ conversation?). The norm around bystander intervention was seen as less entrenched and easier to mobilise communities and campaign around. The participants of the workshop felt also that it could also serve as an entry point to influence more entrenched norms around victim-blaming.

5. Learn from changemakers and map influencers

The process of mapping power and influence needs to be embedded throughout the research and campaign planning process. In Sri Lanka this involved working with local staff and partners to identify the key opinion makers and potential allies to engage in the research process.

and campaigners came together to map out existing information and identify evidence gaps.

Positive outliers, i.e, those who defy the norms, were also an important group to learn from. In particular, young people (aged 18-30) recognised how bystanders could intervene to help and support survivors in confronting perpetrators. According to them, social media has played a positive role in enabling survivors to find support from outside their communities, and the threat of exposure served as a deterrent to perpetrators. This learning was carried forward into the campaign planning, with the creation of the #CreateAScene hashtag to encourage speaking up and calling out perpetrators.

As practitioners, we’d love to hear from others working in this space and lessons to share on how to bridge the gap between research and influencing (particularly around social norms related to issues like ending gender-based violence). Do leave us a comment!

To find out more, read ‘Smashing Spatial Patriarchy’ or visit the ‘Not On My Bus’ campaign page.