Second installment from Heather Marquette

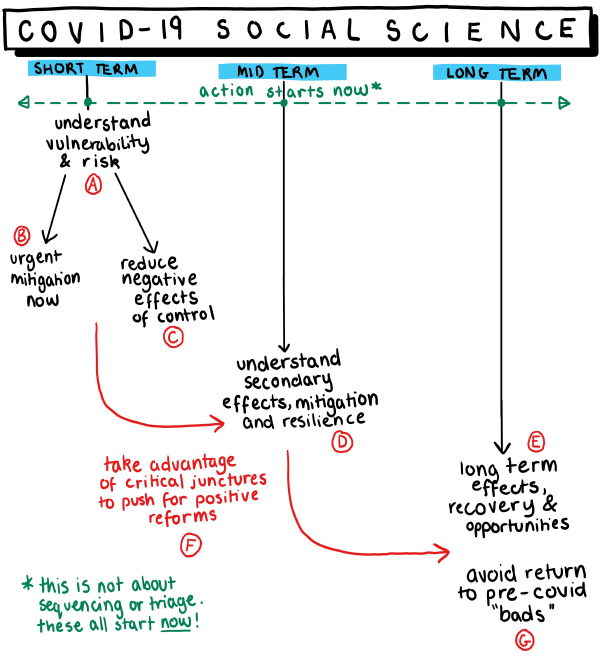

In yesterday’s post, I looked at some of the social and political complexities around Covid-19 and measures to tackle it, bringing in some graphics to try to better communicate what this means and what we need to worry about. Today, one more graphic (an important one, I think) introducing a process to help structure thinking about the short-, mid- and long-term issues and the vital role of social science in understanding this.

Covid-19’s social and political impacts: The future starts now

We know from years of social and political research, including in conflict-affected areas and in complex humanitarian emergencies, that ‘sequencing’ is a myth and that we can’t think about social and political issues in terms of ‘triaging’ – dealing with the most visible issues first. Sometimes it’s the deepest, subterranean cracks that can be the most damaging over time. Globally, the social and political impacts from Covid-19 aren’t second order problems that can be dealt with once the urgent work on flattening the curve and saving lives is done: these impacts are being felt now.

And some of these social and political implications could be the direct result of Covid-19 interventions, whether via the unforeseen consequences of well-intentioned action, or the purposeful actions of authoritarian leaders seizing the moment to ratchet up control, or the differential impacts of the pandemic on men, women and children. Again, I’ve been working with Peter Evans (graphics by Hamsi Evans), to develop a short (urgent)-mid-long-term framework and graphic to help look at the social and political impacts of Covid-19 and measures, as well as potential social science research needs.

Two issues are coming through clearly so far from emerging research and analysis: firstly, the need to ensure we keep a ‘do no harm’ lens in our interventions – bringing in gender, conflict and crime sensitivity and analysis, for example; and secondly, the need for proactive evidence and analysis feeding into intervention design in order to (hold your noses) ‘not let a good crisis go to waste’. While the origin of this quote is contested (used most recently by former Obama White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel), it reminds us that in every crisis there are chances to make better decisions, to ‘do things that you didn’t think you could do before’, and to work hard to ensure that the cracks in the foundations are fixed before the next crisis comes.

The letters here link to the graphic above. Urgent research and high-quality political analysis can help us in the immediate term to better understand where the greatest vulnerabilities and risks are (A) so that we can incorporate appropriate mitigation measures into interventions now (B). At the same time, evidence can help us identify in advance the (potential) negative effects of control measures so that these can be adapted relevant to context in order to avoid negative unintended consequences (C).

In real terms, this means doing urgent things like poverty monitoring, using existing data for rapid modelling of the likely need for social protection, or conducting phone surveys where possible with people with disabilities in order to produce rapid synthesis of the effects of Covid-19 and the Covid-19 response. It means tailoring evidence-based advice on social and physical distancing measures to specific contexts, whether that’s thinking about the needs of key workers or migrant workers, or how social and physical distancing works (or not) in urban slums, or how to deal with the virus in an existing humanitarian crisis, such as supporting already internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the Sahel or small island states facing the ongoing threat of climate change-related flooding.

In this diagram, ‘mid-term’ and ‘long-term’ refer to the impacts, and not the timing in which we need to think about research (D, E). These are the likely impacts, but the time to start thinking about these is now.

Finally, research can help us think and work politically so we don’t miss out on opportunities to ensure much-needed reforms are put in place in order to avoid returning to a ‘normal’ that was in fact bad for many people, the most vulnerable in society in particular (F, G).

Covid-19 is a classic example of a ‘critical juncture’, or cataclysmic events that happen over a relatively short period of time and disrupt the status quo with long term effects. Most of the time, we study critical junctures in the past with the benefit of hindsight, but Covid-19 is so disruptive that we can be in no doubt we’re living through one ourselves. If we can use social and political research to ‘unpack the black box of political will’ and look to better understand the way leaders are – or could be – responding, we may have a chance to seize the awful reality that is Covid-19 as an opportunity to push for positive, much-needed reforms, even against some of the most wicked problems. Indeed, better understanding the opportunities as well as the threats is vital in terms of understanding what can be done, from potential short-term opportunities on. This is how we can better translate what we know about what will likely reduce risks into actions that are feasible, technically as well as politically.

In brainstorming sessions, we’ve started to rapidly apply this short/mid/long-term framework to specific sector or themes – here is a very early run through of thinking on Covid-19 and prisons, as an example:

I’d really welcome your challenge, feedback or suggestions for improvement –comment below or tweet me @hamarquette. If you want to use the template in your own work, please do share what you’ve come up with – a blank version can be found on my website.

Heather Marquette is Professor of Development Politics in the International Development Department, University of Birmingham and is a Steering Committee member of the Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice.